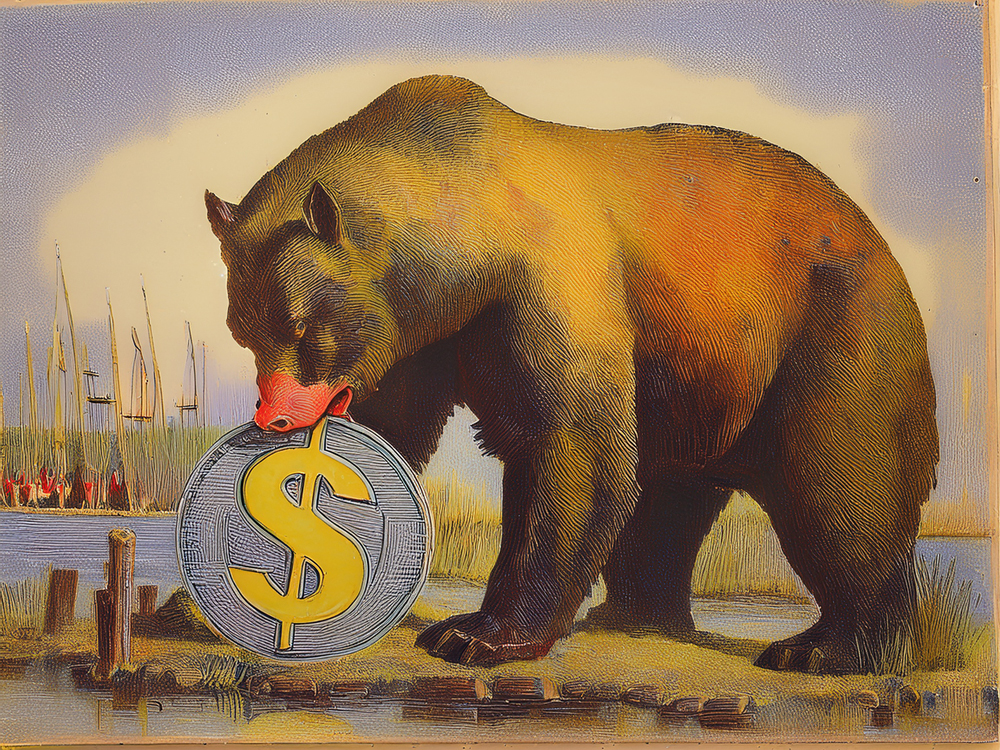

Recent headlines shouted that the U.S. Dollar Index, which measures the greenback’s performance against a basket of developed country currencies, fell 10.8 per cent in the first half of 2025—its worst performance since 1973. That is a startling statistic, but it presents more questions than answers about the outlook for the U.S. dollar. For instance: Is the dollar’s drop a bad thing, or the deliberate result of U.S. trade policy? Is the decline accelerating, or will the dollar bounce back? And is this a sign that the greenback is falling from its perch as the world’s preferred reserve currency?

Unfortunately for global investors, the answers are far from straightforward. Here is a best shot at some of the most commonly asked quandaries about the outlook for the U.S. dollar, based on the opinions of experts:

Is the U.S. dollar’s time as a reserve currency limited?

We need to go back more than 80 years to understand the context on this one.

The Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944, in which 44 allied nations agreed to create a fixed currency exchange rate using the gold standard, helped cement the U.S. dollar’s reserve status by pegging the currencies of other countries to it and promising to back each dollar with gold at a set rate of US$35 per ounce. (A reserve currency is a foreign currency held by governments and central banks as part of their foreign exchange reserves.)

In 1971, President Richard Nixon’s decision to abolish the gold standard sent shockwaves through global financial markets. When global leaders met with Treasury Secretary John Connally, they sought assurances that they wouldn’t be stuck holding a currency that the U.S. could simply inflate at will. Connally’s reply: “Well, it’s our dollar, but it’s your problem.” (The incident inspired American economist and Harvard professor Kenneth Rogoff to title his recent book Our Dollar, Your Problem: An Insider’s View of Seven Turbulent Decades of Global Finance, and the Road Ahead.)

Despite the turbulence of the early 1970s, the dollar has remained the world’s undisputed reserve currency because of a combination of forces: confidence in the country’s economic strength and performance, the need for exchange rate stability, the nation’s influence and stability, and its broad capital markets. When that reputation gets battered, confidence wanes.

Which is what appears to have been happening this year—to a certain extent, at least. But the loss of dominant reserve status for the greenback is likely to be a long and drawn-out process, if it occurs at all.

“The U.S. dollar is poised to be knocked down a couple of pegs,” Rogoff says. “But it will still be first in global finance, because nothing is poised to fully replace it. The dollar just won’t be as unique as it once was.”

Rogoff’s 10-year outlook for the U.S. dollar sees a potential mix of currencies filling the gap as countries such as China become more important to Asian trading partners.

“For example, the euro will rise to 30 per cent of reserves from the current 20 per cent, the yuan will rise to 15 per cent from the current near-zero, and the U.S. dollar will fall to 40 per cent” from nearly 60 per cent last year, he hypothesizes. “Cryptocurrencies will also play a role in the underground economy.”

Trump II has added a decade to the dollar’s effective age.

Kenneth Rogoff

Angelo Kourkafas, senior investment strategist with Edward Jones, agrees.

“The dollar remains the world’s reserve currency simply because there’s no alternative,” he says. “About 80 per cent of all daily currency transactions taking place worldwide are still made with the U.S. dollar.”

Kourkafas also throws cold water on the importance of some central banks dumping their dollar reserves.

“Despite these outflows, we have seen very strong inflows from private investors,” he says. “I believe inflows from private investors have actually been greater than the central bank selling that has recently occurred.”

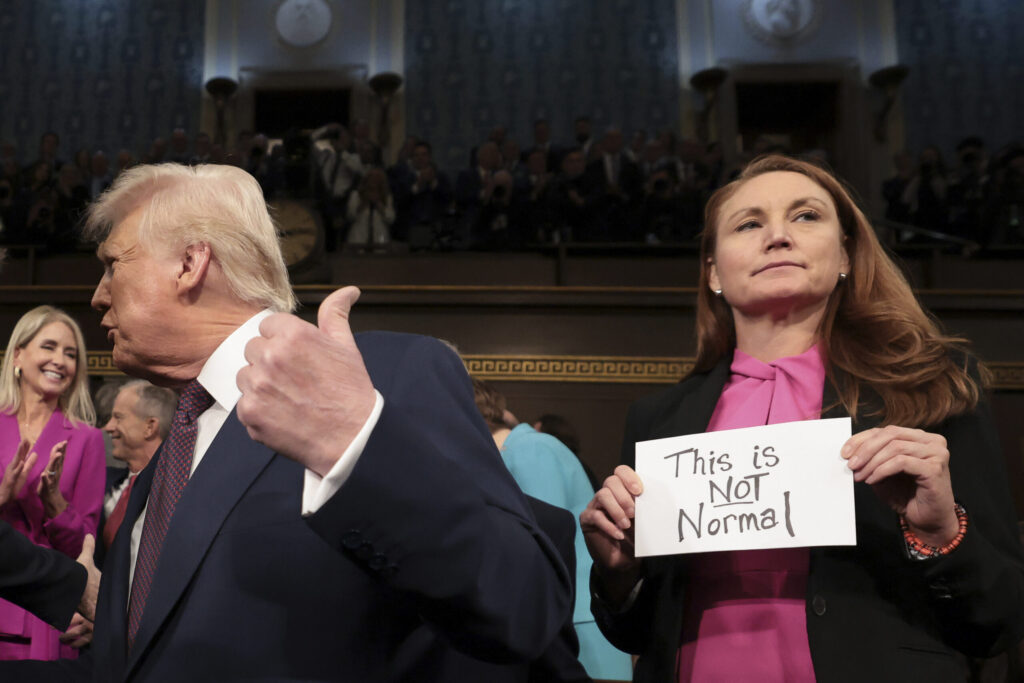

Have recent U.S. policies hastened the dollar’s demise?

Rogoff recently described the dollar as being in “late middle age, but still in good health.” Global tariffs and other policies established during President Donald Trump’s second administration have changed his prognosis.

“Trump II has added a decade to the dollar’s effective age,” he says.

Tom Nakamura, vice-president and portfolio manager, currency strategy and co-head of fixed income, AGF Investments Inc., says he agrees.

“Trump’s second-term policies have eroded investor confidence in the U.S.,” he says. “More importantly, other countries have responded by focusing on resource development and economic independence, prompting a rotation of investment flows away from the U.S.”

As the issuer of the world’s reserve currency, the U.S. enjoys the benefit of lower long-term borrowing costs to finance its debt. Foreign countries like to hold U.S. Treasury bonds, which the U.S. government can issue at will due to high confidence in the government to stand behind them. When excessive debt and economic slowdowns reduce confidence in a country’s economy, confidence in its currency may also decline. A policy of unsustainable U.S. government debt may also be fueling the current currency decline.

But any policy-related diminution of the dollar’s reserve status will probably come slowly. Nakamura explains that the recently released Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) by the International Monetary Fund suggests that the share of U.S. dollars in currency reserves held steady in Q1 of 2025.

[The dollar] has simply unwound the outsized strength we have seen in recent years.

Tom Nakamura

“The release of Q2 data may be more insightful, but we expect that if there is an adjustment afoot, it will be gradual and span many quarters if not years,” he says. “More tortoise than hare.”

Is the U.S. dollar currently undervalued?

“We have thought the U.S. dollar has been overvalued for more than the last two years and have been increasing our CAD-hedged positions inexpensively during that time,” says Arthur Salzer, chief executive officer and chief investment officer of Northland Wealth Management. “However, we were uncertain about the conditions that would cause the mean reversion. Given the headline risks of the Trump Administration’s tariff policies combined with the ‘big, beautiful bill,’ policy-driven risks appear to have been sufficient to weaken the greenback recently.”

Kourkafas says the dollar’s near- and long-term performance may also diverge.

“In the near term, the dollar has moved very far, very fast, so it would not be surprising to see a relief rally, and we have started to see that,” he says. “Looking at several long-term valuation metrics, the U.S. dollar is still overvalued relative to other major currencies. The dollar bull market has lasted almost 15 years, but potentially some of the factors that have driven it higher may be starting to reverse. The U.S. economy outperformed the Canadian and other major economies over the last couple of cycles, but the growth gap between the U.S., Canadian and Eurozone economies is starting to narrow for 2025.”

Nakamura says that the weaker position of the U.S. dollar is largely justified.

“It has simply unwound the outsized strength we have seen in recent years,” he says. “While there is likely to be some volatility and short-term profit-taking on U.S. dollar shorts, we expect the dollar to continue to weaken in coming months.”

Is the U.S. deliberately weakening its dollar?

Some economists argue that the Trump administration is pursuing policies designed to weaken the U.S. dollar, making imports more expensive and exports less expensive as part of an effort to rectify perceived trade imbalances. (On the counterargument side, the incoming foreign investment Trump has demanded in his trade “deals” so far, with Japan and the European Union for example, would tend to support the dollar.)

“While the U.S. administration has denied they are pursuing a weak dollar policy, the sum of their initiatives suggests to us that they are at least tolerant of some weakness,” Nakamura says.

In the 1960s, Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin identified the Triffin Dilemma, which posits that countries issuing the world’s reserve currencies must supply the global economy with enough currency to keep the world’s economic engine ticking. Ending the U.S. gold standard in 1971 allowed the U.S. to do exactly that, by issuing more currency than its gold reserves allowed. However, that eventually results in trade and balance of payments deficits, which in turn can undermine faith in that currency’s reserve status.

Trump recently fired a volley at the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, plus Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates) by threatening them with additional tariffs if they attempted to create a new global reserve currency. That suggested, perhaps, that the U.S. is in no hurry to lose its reserve status and the “big stick” it provides to influence other nations through trade sanctions and other forms of economic warfare.

So, which is the priority? Can the U.S. pull off a hat trick by lowering the value of the dollar and improving its balance of trade, all the while retaining its status as the world reserve currency?

“It’s likely that there will need to be a compromise on at least one of the priorities,” Nakamura says. “A slow decline in the U.S. dollar’s role in the world’s reserves may have some appeal, but the transition needs to be slow and gradual. Any official acceptance of it would be dangerous and reckless for the U.S. administration. A disorderly shift would not only destabilize the dollar and currency markets broadly, but also create issues in the U.S. Treasury bond market and other asset markets.”

While government policy can have a significant effect on currency valuation, Kourkafas says that power is limited.

“Ultimately, it’s the market that’s going to determine the value of the U.S. dollar, instead of what the administration wants to happen,” Kourkafas says. “I would point to economic growth and interest rate differentials as the primary drivers.”

Cryptocurrency to the rescue?

The recent passage of the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins (GENIUS) Act establishes a regulatory framework for stablecoins—a kind of cryptocurrency backed 1:1 by U.S. dollars or Treasuries.

“This ground-breaking technology will buttress the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency, expand access to the dollar economy for billions across the globe, and lead to a surge in demand for U.S. Treasuries, which back stablecoins,” crowed Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent after the act was passed. “The GENIUS Act provides the fast-growing stablecoin market with the regulatory clarity it needs to grow into a multitrillion-dollar industry.”

Salzer, for one, says that could support the greenback going forward. “Were it not for the GENIUS Act, we would be expecting a significantly weaker U.S. currency,” Salzer says. “Stablecoins lower barriers to holding and transacting in dollars, requiring only a smartphone. This is particularly impactful in emerging markets, where high transaction fees and currency exchange restrictions limit dollar access. For instance, stablecoins already facilitate over $700 billion in monthly transactions, with 90 per cent of the $243 billion in circulation being U.S. dollar-denominated.”

Driving significant demand for U.S. debt and for short-term Treasuries could reduce yields, lowering the U.S. government’s borrowing costs, Salzer says. However, while the increased demand for Treasuries could reinforce the dollar’s role as the world’s primary reserve asset, concentration of Treasury holdings among stablecoin issuers could also reduce the U.S. Federal Reserve’s control over short-term interest rates, posing challenges to monetary policy.

“While we expect additional volatility in the dollar over the next year to 18 months, we are less bearish looking forward than we normally would have been,” Salzer says. “The GENIUS Act provides a potential tailwind to the U.S. dollar over the remainder of this decade and into the next.”

Nakamura is less bullish on the future of U.S. dollar-backed stablecoins.

“They would need to be widespread globally and supplant the trade that has already moved away from the U.S. dollar,” he says. “We don’t think that this is likely in the current environment.”

The upshot for investors

Few economists expect sudden, seismic shifts in the reserve status of the U.S. dollar. Accordingly, Edward Jones doesn’t recommend investors engage in sudden shifts in their portfolios based on fears around the short-term performance of the greenback.

“We recommend a slight overweight of U.S. large- and mid-cap stocks based on the relative outperformance of earnings, which is a powerful driver,” Kourkafas says. “Artificial intelligence and some of the growth exposures continue to deliver. But we know that many investors have a very low allocation to overseas equities relative to what we think should be an appropriate strategic asset allocation. Recent changes in currency trends are one consideration, but over the long term we would point more to fundamental strength in economic growth and corporate profits.”

The fate of Canada’s currency may also affect outcomes for Canadian investors.

Nakamura sees “constrained optimism” for the Canadian dollar, noting that, while Canada’s economy has held up reasonably well under tariff uncertainty, painful economic adjustments may await on both sides of the border.

“Additionally, there will be pressure on Canada’s fiscal picture, which may act to deter inbound investment in the short term,” he says. “Our negative view on the U.S. dollar offsets this, and we think a moderately lower USD/CAD rate of 1.33-1.34 is likely. All else being equal, a stronger Canadian dollar creates a currency loss on foreign holdings. A well-diversified portfolio that incorporates active currency management can help navigate risks and opportunities.”

The last word on reserve currencies …

… belongs to history itself. One day, the U.S. dollar will quite probably join the drachma, the denarius, the solidus, the dinar, the florin, pieces of eight, the guilder and the pound sterling in their fall from grace. That time is not yet. Countries seeking to replace it with their own currency should hope they can achieve that goal gradually—and can live up to the burdens of reserve status as well.

Peter Kenter is a Toronto-based writer with a deep and abiding interest in how everything in the world works and how it got that way. He’s written about the economy, investing, financial services, cryptocurrency, pharmaceuticals, mining, energy, cannabis, agriculture, consumer electronics, education, sponsorship marketing, and entertainment. He’s the author of TV North: Everything You Wanted to Know About Canadian Television. He loves English bull terriers.

Please visit here to see information about our standards of journalistic excellence.