After years of working in finance and fintech, Chantel Chapman expected her own financial expertise would help resolve the problematic behaviours she was noticing in her own relationship with money—overpaying for things she couldn’t afford, under-charging for work, and going into workaholic mode.

Her financial knowledge didn’t change her habits, so she asked a therapist for help, only to be told: “We don’t get trained in money.” With no financial or therapeutic support in sight, Chapman decided to build her own, and the Trauma of Money Institute was born.

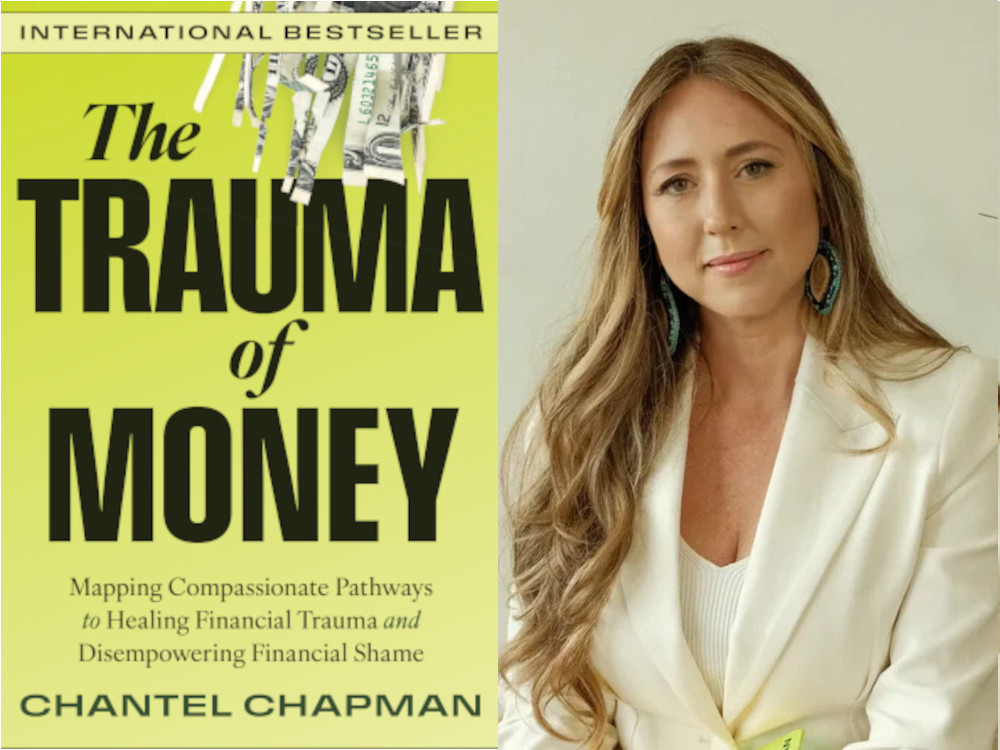

Chapman’s new book, The Trauma of Money, is a digest of the educational program, which teaches a trauma-informed approach to improving one’s relationship with money. It offers a professional certification, too. It is among the top non-fiction best-selling books in Canada.

“The essence of what we do is teach people to decrease shame and increase discernment around money,” says Chapman, who lives in Tsawwassen, B.C. “We pull from a lot of areas, including the world of financial psychology. We pull from the world of trauma, recovery and addiction recovery, while also looking at the impacts of the economic systems that we live in.”

We’ve had a major influx of wealth advisors and family offices and financial consulting institutions coming in.

Chantel Chapman

Why the therapeutic lens and language? Chapman explains that her childhood experiences with poverty and trauma were causing problems with how she handled money. “I was noticing all these behaviours,” she says. “But no amount of understanding of how financial systems work actually shifted the behaviours.”

She embarked on a multi-year research journey to find the connections between financial behaviour, psychology and trauma, and “that’s essentially why this book and the course take that approach.”

Chapman says the educational program she launched in 2018 was aimed at wealth advisors, but the mental health community, desperate for financial training, came flocking first. Today’s audience is broader.

“We’ve had a major influx of wealth advisors and family offices and financial consulting institutions coming in,” she adds. After all, affluence provides no immunity to emotional challenges. In fact, it can exacerbate them, experts say.

Scarcity mindset and financial shame

Though money trauma, she says, is income-agnostic, her book spells out the kinds of behaviours ultra-wealthy people might exhibit when it comes to money, and how to resolve them.

Chapman talks a lot about financial shame and says high-net-worth individuals experience it along with everyone else. Rooted in traumatic experience, financial shame can manifest itself as perfectionism, which can start an unhealthy cycle of procrastination, avoidance and, ultimately, more shame.

Wealthy people are not immune to the psychology of scarcity, either. Your brain doesn’t know the difference between perceived scarcity and actual scarcity, says Chapman. It’s a mindset you can pick up from your family and even your family’s past.

“If the wealth creation in your family occurred after an extended period of scarcity, there might be some deeply ingrained behaviours around resources that are rooted in a scarcity mindset,” she says.

“We know that scarcity mirrors a trauma response in the brain. So, if your brain believes it’s in a state of scarcity, you’re going to experience reduced cognitive capacity.”

A scarcity mindset can lead to poor impulse control and decision-making, she says.

Why ‘trauma’?

Chapman says people in the financial world don’t like the word “trauma.”

“Sometimes we’ll have a financial institution hire us and they’ll say, ‘Hey, don’t call your training ‘The Trauma of Money.’ Let’s call it, like, the ‘psychological barriers behind wealth’ or something like that,” Chapman says.

The word, she insists, is misunderstood. People think it implies the worst possible experiences: war, abuse or serious bodily harm.

Trauma, she says, is any wound or injury that affects your sense of security. Your brain categorizes the experience as dangerous, and then responds to any similar situation by sending you into survival mode. This is a trauma response, in which your brain is budgeting resources to help you survive.

It can result in bad decision making, black and white thinking, avoidance and a host of other behaviours, she adds. Regardless of what causes it, it’s crucial to understand the behaviours that result from trauma in order to move past them.

Blurred boundaries and interdependence

Financial enmeshment is another common effect of money trauma among high-net-worth people. In this scenario, Chapman says, boundaries become blurred, creating an unhealthy interdependence.

“It’s easy for the parent who holds the wealth to overstep where their adult children are concerned,” she says. “It’s hard for the child to see: ‘Where do you start, and where do I end?’ This can lead to problematic behaviour from children who are trying to create independence from their parents. It becomes a feedback loop where the parents step in to be even more controlling.”

What might a financial advisor take away from Chapman’s teachings? One is the ability to identify shame, which is easy to mistake for laziness, anger or even arrogance. Another is how to create the trust needed to support the person who’s experiencing shame.

“This is very important for high-net-worth people, because one of the things that we see a lot is the hesitation to trust certain relationships,” she says, “which is directly correlated with the amount of wealth they have.”

Ultimately, Chapman says, everyone has what it takes to be good with money, regardless of income.

“To believe that you can be trusted with money doesn’t mean that you’re all of a sudden going to become a day trader for your large financial portfolio. Or that you’re not going to use any advisors,” she says. “Actually, it means that you know how to choose the right person to work with.”

All of us should believe that we can be trusted with money. “And that requires you to align with your values about what money means, what you want to do with it and how you interact with it,” she adds. “That’s true across all levels of wealth.”

Cindy McGlynn is a Toronto-based writer and editor who frequently writes about business, culture and the arts. In addition to holding communications roles at tech startups and writing for consumer and B2B publications, Cindy has edited two national magazines and served as a long-time columnist for the Toronto Star’s Eye Weekly magazine. She has been contributing to Canadian Family Offices for four years.

The Canadian Family Offices newsletter comes out on Sundays and Wednesdays. If you are interested in stories about Canadian enterprising families, family offices and the professionals who work with them, but like your content aggregated, you can sign up for our free newsletter here.

Please visit here to see information about our standards of journalistic excellence.