From copper to cobalt to rare earth elements, critical minerals are in demand worldwide to power the energy transition, digital technology and even defence applications. And Canada is potentially poised to take advantage of the move toward a more sustainable supply.

While some investors are already finding compelling opportunities in the Canadian market—whether they are explorers, producers or infrastructure suppliers—others are keeping close tabs on rapid policy developments in this space before moving ahead.

Demand for key critical minerals—including lithium, graphite, nickel, cobalt, rare earth elements and copper—is projected to grow significantly in the next 15 years, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). This will require substantial investment in new mines and refineries to the tune of around US$500 billion by 2040.

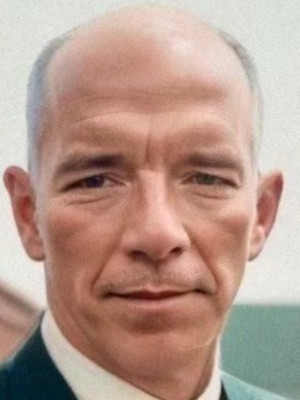

At the G7, all of the countries said they wanted to buy Canadian critical minerals.

Tim Hodgson, federal minister of energy and natural resources

China is the dominant refiner of 19 out of 20 energy-related minerals, with an average market share of 70 per cent. This has left the market vulnerable to supply shocks and price volatility and led many countries to try to secure supply.

Canada has the goods

But Canada has the potential to be a major global supplier, says Ben Jang, a portfolio manager with Nicola Wealth in Vancouver.

“We have over 30 minerals defined as critical. We have top reserves in nickel, cobalt, graphite and lithium, and when we take a look at Canada, it’s a trusted supplier to the world, given our lower geopolitical risk,” he says.

While Canada boasts reserves of the six highest-priority minerals with an estimated value in the billions of dollars, getting them out of the ground is another matter, according to a recent report from the Canadian Climate Institute (CCI).

Permitting delays, a lack of infrastructure and volatile prices for minerals have historically acted as barriers to investment at both the capital markets and project levels.

Canada is already a major supplier of certain critical minerals to the U.S. and other countries, but only a fraction of our resources have been produced, says the CCI. Meeting expected demand growth in Canada alone will require investment of as much as $30 billion by 2040 and $65 billion to meet growth in global demand—that’s more than 30 new mines, according to the CCI.

Recent moves to encourage investment

At this summer’s G7 meeting in Kananaskis, Alta., leaders recognized the risks to the resilience of critical minerals supply chains, creating the G7 Critical Minerals Action Plan. The initiative focuses on “diversifying the responsible production and supply of critical minerals,” encouraging investments in projects and developing a roadmap to promote standards-based markets.

In other domestic developments this year, the federal government committed more funding under its critical minerals strategy “to support infrastructure development, innovation and data collection” in consultation and partnership with Indigenous communities.

In addition, the Building Canada Act within Bill C-5 will allow the government “to urgently advance” projects that are in the national interest, including those that enhance the development of Canada’s natural resources and infrastructure.

In a recent speech to the Toronto Region Board of Trade, Tim Hodgson, federal minister of energy and natural resources, said the legislation creates the conditions to get more projects off the ground. “At the G7, all of the countries said they wanted to buy Canadian critical minerals,” he said. “This is an opportunity for us.”

The country’s financial and mining sectors are looking to the government to create industrial policy that streamlines the consultation process, clears permitting bottlenecks and helps companies commercialize deposits, says Benoit Gervais, senior vice-president, portfolio manager and head of the Mackenzie Resource Team at Mackenzie Investments in Toronto.

These efforts, he says, are coming together.

“Probably in the next two years we’ll have the policy, and then in the following two years we’ll have decisions. I think the industry’s already working with that notion that it will be easier, so they’re preparing projects,” Gervais says.

“We’ll put shovels in the ground before the end of the decade.”

Investment opportunities in critical minerals

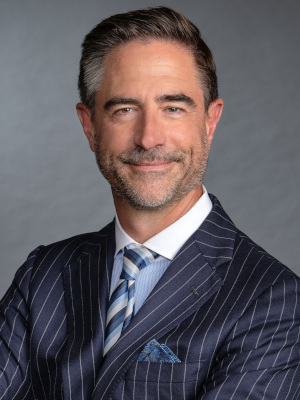

Brian Madden, chief investment officer with First Avenue Investment Counsel Inc., an investment management firm and family office in Toronto, takes a broad view of the critical minerals space. He includes lithium, nickel, chromium and copper but also fertilizer, uranium and even gold.

His firm’s wealthy clients are generally interested in investing in producing projects, he says, but they lack the risk appetite for earlier stage developers.

Canada is already poised to take advantage of demand, he says.

For example, with a nuclear renaissance of some note underway, Madden is investing in uranium via equity ownership of Cameco, which operates two producing mines in Saskatchewan and boasts nuclear enrichment capabilities.

He is also invested in potash miner and producer Nutrien, given the U.S. demand for Canada’s potash exports. “It is maybe a bit outside of the mainstream usage of the term ‘critical minerals and metals,’ but certainly there’s no doubt that these things are indispensable if we want to feed a hungry planet,” he says.

Madden says he is also watching for further action from the federal and provincial governments. “We need to get these nation-building projects’ shovels in the ground and permits issued and social licenses achieved. And that’s easier said than done.”

For projects with economic potential, such as Northern Ontario’s Ring of Fire—an area with vast reserves of critical minerals for which the provincial government has pledged to streamline permit approval processes and create a new Critical Minerals Processing Fund—Madden’s team is opting to invest in infrastructure rather than directly in extraction.

“We think the responsible way to play those deposits getting developed is sort of a second order effect, which is to invest in a profitable company that can help build up the critical infrastructure,” says Madden, who holds an equity ownership in construction and engineering firm WSP Global.

Jang points out that another way to invest in this space, at least on the mining side, is royalty streaming companies. “They benefit because they have lower operational risk and strong cash flows,” he says.

Higher-net-worth individuals can also gain exposure to the sector by participating in flow-through shares, he says, which offer tax deductions and credits for investment in junior exploration, mining and mineral processing companies. Earlier this year, the federal government announced a two-year extension of the 15 per cent Mineral Exploration Tax Credit for investors in flow-through shares.

In terms of investment opportunities in critical minerals, Gervais and his team of analysts are working on their own studies to identify potential geographic clusters of activity that may require just a small push over the line.

“I think the government is in a hurry. They wanted those projects yesterday. So, I think that if you can find those, then you can probably move ahead and make some investments with the likelihood of success probably higher,” he says.

Ultimately, Gervais expects more activity in this space within the next two years.

“Part of the allure of this industry is that, I think, there will be big winners,” he says, “and they’ll create a lot of alpha for those who manage money.”

The Canadian Family Offices newsletter comes out on Sundays and Wednesdays. If you are interested in stories about Canadian enterprising families, family offices and the professionals who work with them, but like your content aggregated, you can sign up for our free newsletter here.

Please visit here to see information about our standards of journalistic excellence.